The Japan Philippine Economic Partnership Agreement is like a meeting between Mike Tyson and Manny Pacquiao, one big, the other small; and the terms of their meeting also appear inequitable in favor of Tyson against Pacquiao. It is a partnership favorable to Japan, disadvantageous to the Philippines.

Why? Because, among others, it unjustifiably seeks to grant national treatment to Japanese investments. Article 89 of JPEPA says that each party shall accord to investors of the other party and to their investments treatment no less favorable than that it accords, in like circumstances, to its own investors and to their investments with respect to the establishment, acquisition, expansion, management, operation,, maintenance, use, possession, liquidation, sale, or other disposition of investments.

Traditionally, an alien investor comes into the nation of another, with resources to do business. He enters like a guest, abides by the laws of that nation during his stay, and liquidates his undertakings when he decides to, in accordance with domestic regulations.

What does national treatment mean? Does it ask that we regard the Japanese investor as we do our own Filipinos? Does it connote parity, same as the parity we extended to US firms and citizens equal to Philippine firms and citizens in the wake of rehabilitation in l948? No. National treatment means more. It does not merely refer to equal -- but also to treatment no less favorable than that we accord to Filipinos under like circumstances. The treatment can be equal, can be more favorable to the alien investor -- but not less favorable. If for example there exists an area in Mindanao such as a preserved zone which prohibits the establishment of business therein, we can rightfully deny applications of both Philippine and Japanese to do business there. But if we grant the request of both yet give more privileges to the Japanese investor, that could be unjust but okay under JPEPA because the treatment is more favorable to the Japanese investor.

Where would national treatment apply? Not in Japan where there hardly exists any Filipino businesses, but here where Japanese investments abound. As worded in JPEPA, national treatment would cover practically all areas of investment – from establishment, to operations, to sale, to liquidation.

JPEPA is an unequal treaty because it will operate one sidedly in favor of Japan.

In the case of National Treatment, this means that Japanese investment in the Philippines become the major components of our national economy, to be treated more than parity. Under JPEPA the Philippine government becomes the guarantor of Japanese investment, against political risks like revolution. If a Japanese factory is destroyed in the wake of that revolution, the government under the terms of that treaty pays compensation. If, on the other hand, a Filipino factory is destroyed, no such warranty exists.

There is bigger folly. It appears that the Philippines did not ensure the needed flexibility. In Annex 7 we did not make more comprehensive reservations. We referred to some limitations imposed by the constitution -- but we did not reserve our right to enact future legislation. On the other hand, Japan’s reservations are extensive – covering national treatment, most favored national treatment, prohibition for performance requirements – and expressly made the reservation to adopt or maintain any measure relating to those areas.

In basic agreements, especially where new rights are invoked such as national treatment, it is fundamental that reservations be made clearly because no reservations made means conformity to the new relationship, with no more recourse in the future to complain – and where congressional rights are affected – there may result a relinquishment by congress to exercise remedial powers to correct a wrong.

For example, we did not make any reservation on public utility. Would this mean that Japanese firms, if JPEPA is approved, can now enter that vital area and be accorded national treatment? Seems so, because we did not make a proper reservation.

In fisheries, our reservation states that no foreign participation is allowed for small scale utilization of marine resources in archipelagic waters, territorial sea and exclusive economic zone. In the second paragraph, it states that for deep sea fishing, corporations, associations or partnerships with a maximum 40% foreign can enter into co – production, joint venture or production sharing with the Philippine government. Compare this with the Japanese reservation which details the subsectors of fishing and states that Japan reserves the right to adopt or maintain any measure relating to investment in fisheries in the territorial sea, internal waters, exclusive economic zone and continental shelf of Japan.

The first part of our reservation implies that the prohibition fishing in our waters apply only to small scale fishing, without clear restraint on other activities. Under this loose and incomprehensive reservation, a Japanese fishing boat factory can conceivably establish fishing operations in our waters, with or without JPEPA. The second part of our reservation is likewise inadequate. It deals only with agreements with government. What of the continental shelf? What of economic development in the exclusive economic Zone?

For lapses in making proper reservations, we may forego rights, relinquish power to enact future legislation on investments. Therefore we should not approve JPEPA. Why deprive congress of this fundamental right of legislation embodied in Art.Vl Sec. l of the constitution.

A treaty is intended to enhance the nation, not derogate its power to govern. Ironically, Art.4 of JPEPA calls on the parties to consider amending or repealing laws that affect the implementation and operation of said agreement. – For us to further relinquish legislation? To further ensure protection of their investments? But if there arises abuse detrimental to national interest, should we not assert to correct a wrong and use legislative power? We cannot and should not give up this inherent right to fight for the Filipino. Even the power of local governments are affected. Instead of more autonomy, one year after approval of JPEPA, they will be restrained from enacting ordinances concerning Japanese investments. JPEPA will operate as a usurpation of legislative and executive powers of the Philippine government. It creates a hierarchy of rules in our legal system in which JPEPA will hold a position of supremacy over the acts of Congress. JPEPA is at war with the principle which our own Supreme Court upholds: that a statute and a treaty one of equal understanding in our legal system..

2. Under JPEPA, all products are targeted over time for tariff reduction or elimination, all – except those exempted. Japan listed 238 tariff lines involving various agricultural and industrial products such as sardines and slippers for exclusion while the Philippines limited exemptions to only 6 tariff items, 5 for rice and l for salt. This means that once JPEPA is approved, the targeted reduction or elimination of tariffs of all products outside the exempted ones will begin. The Philippines agreed to reduce or eliminate tariffs in ten years, Japan within 3 to l5 years, with some goods like sugar still quantified under a Tariff Rate Quota..

In accordance with articles l2 and l3 of said agreement, the implementation of JPEPA will be done by a Joint Committee and sub coommittees composed of representatives of the Government of the parties, But the power over tariffs in the Philippines is vested in Congress, not to any joint committee. The President who signed the proposed agreement possesses only delegated powers – and the same cannot further be delegated.

The moment JPEPA is concurred in by the Senate it becomes valid out effective as law and the Supreme Court has categorized a treaty concurred in by Senate as domestic law. In this light, the operation of JPEPA through the Joint Committee and several sub-committees becomes a situation where Japanese government appointees will be engaged in the implementation of a domestic law in Philippine territory ─ a bizarre anomaly in our constitutional and legal system.

Where is accountability? Responsibility? Transparency? The negotiations that led to JPEPA were done in relative obscurity, without the needed information and publicity mandated by the right to know. It is a truism that in bilateral negotiations, the poor who possesses less bargaining power must be ten times more vigilant, otherwise concessions can be easily taken in the guise of aid like Official Development Assistance. We do not depreciate the Assistance given to the Philippines by ODA. But such assistance are loans that Philippines pays for. In addition there exist flow back benefits that Japan gets back because the entity in charge of ODA, Japan Bank and International Cooperation, mandates that the majority of the projects funded by said Assistance must be undertaken by Japanese entities. If Japan waved the flag of ODA before, they can do it again during implementation once JPEPA is approved. The Joint Committee to implement presumes equal partners out to pursue equitable interests. But reality tells us that in such situations the perceived welfare of both do not run parallel but often collide. So this kind of implementation may only retard, not smoothen relations. Furthermore, under JPEPA, the most favored treatment clause is extended to other countries. If we extend national treatment to their investments, the same can be invoked by other nations in separate agreements. We may have multiple joint committees overseeing similar JPEPAS for as many countries – a financial and administrative nightmare!

In the meantime, Japan under the proposed treaty denies us tariff reduction for agricultural goods to enter her country such as sugar, bananas, mangos, tuna and other marine products even as we give duty free imports to her industrial inventories like electronics - for double whammy advantages because many of these products or their parts are manufactured in the Philippines by Japanese firms themselves, like transmissions for automobiles. They ship them from here to Japan duty free, and when they export an entire automobile, transmission included, they will come in one day duty free. Japan exports to us high value finished goods, usually accorded low tariffs. The Philippines on the other hand trades low value added rural products like banana – yet we must pay tariff of ten to twenty percent. An imbalance we can ill afford. As of 2005 our trade deficit with Japan already stood at $2,034 billion US dollars. JPEPA will predictably see more imports from Japan, shifting our focus from manufacturing to importing and losing jobs to workers.

. 3. What is even of greater concern is the dumping of Japanese materials such as hospital waste, municipal sewage, clinical toxics, and other materials embedded in products which will come in duty free. In l999 Japan exported to the Philippines in a single try, l22 40 ft container vans -- reportedly carrying waste paper for recycling. However, when the container vans were opened, what the government authorities found was not recycled paper as stated in the customs declaration – but hazardous, infectious, and toxic trash: intravenous injections, used diapers and napkins, syringes for blood, dextrose, worn bandages. We protested because it was the right thing to do, and after some ado, the perilous products were sent back.

Japan is highly industrialized. She generates many products that contain chemicals and toxic waste. For her own ends, she has adopted a policy of the three Rs: Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. This means they are encouraged to use products like a ferry boat for commercial purposes, and after some time recycle by converting it, perhaps into a tugboat, then when no longer viable, dump them somewhere. Including the effluents and enamels embodied therein.

Waste disposal comprises a big challenge, and the principle enunciated by the International Basel Convention, an assembly where both the Philippines and Japan are members -- is that each nation maintains within its own borders the responsibility of resolving the waste problem. There grew a glaring loophole when some developed nations claimed they were not exporting waste but recycled products.

The international community via the Basil Ban Amendment plugged that loophole preventing the transborder movement of toxic and hazardous waste even for recycling. Unfortunately neither Japan nor the Philippines has ratified the Basel Ammendment. But the Philippines should, because we have laws which control the use of Toxic Substances and Hazardous Wastes, Republic Acts 6969 and 4653. If however we approve JPEPA, we set aside our own laws – and open our doors to garbage disposal. Does not our nation deserve the right to health against hazardous waste? Are we not concerned first and foremost with national interest? Do we not have enough of a problem in the disposal of our own waste?

The advocates of JPEPA claim that Japan has entered into similar agreements with countries like Malaysia and Singapore which are beneficial. But Malaysia has ratified the Basel Agreement, while Singapore is a noted center of transshipment for commercial trade.

In our case, our negotiators have agreed to adjusted tariff rates, setting the stage for Japan - to dump their recycled garbage here, no matter the consequences. The tariff for waste pharmaceuticals has been lowered from 20% to 0; municipal waste from 30% to 0; clinical waste such as adhesive dressings, wadding gauze, surgical gloves from 30% to 0. Waste comprising organic solvents, halogenated substance, from 305 to 0. The reduced tariff to zero – glares like an ugly invitation for Japan to dump.

JPEPA refers to the products of trade as goods but the ‘bad ones’ are left hanging. If a forty foot container van export arrives comprising 60% used newpapaers but 40% recycled worn out products containing perilous effluents, will our customs officials reject the waste and admit only the old newsprints, considering that implementation of JPEPA is under a joint committee under the demanding rules of GATT adopted by JAPEPA?

We are told that our Foreign Affairs Secretary has written a letter to his counterpart, the Foreign Minister there, who responded that Japan would not export hazardous waste to our country. But such letters were not included in the negotiations, not made integral parts of the agreement, not definitive of what constitutes forbidden waste – because for Japan a recycled product is a product that can be exported. If they genuinely desire not to export waste to the Philippines then we should amend the treaty.

4.Those for JPEPA proclaim that for some concessions in trade, the door for Philippine nurses and caregivers will now open. They say it is an opportunity for a better life. If so, then why do the members of the Philippine Nursing Association themselves stand opposed to JPEPA?

The entry of nurses and caregivers there are totally governed under the Immigration laws and regulations of Japan. We do not know how many are entitled to go, when, for how long. Philippine Nurses and caregivers have been acclaimed the world over. Not only do they ably discharge their duties in a dedicated way, they do so with a personal touch, regardless of overtime and overdue pressures. To make them learn to speak and write in Nipongo seems reasonable – but they object to the requirement that they take another qualifying examination again – in Nipongo. To learn and communicate in an alien tongue is alright, but what looks unfair is to have them undertake a rigorous examination in Nipongo, whose nuances they do not fully grasp, where even amongst Japanese applicants the success rating is not relatively high. At present professional Japanese coming here in aid of their firms doing business in the Philippines are accorded fair treatment. Would they not object if the host government impose as an additional requirement for their stay – that they also take a qualifying examination in Filipino?

What happens when a Filipino applicant for nursing does not qualify? How long can she stay, what kind of treatment to expect? Can the rules change? The questions are relevant because JPEPA is an agreement not only in trade and investments but also to treatment of natural persons, governed by Japan’s laws and regulations in immigration.

5. GATT, the General Agreement on Tariff and Trade, and its successor, the WTO, World Trade Organization, were the entities that sponsored globalization. Their vision got derailed because of the resounding cries of protest raised mainly by developing nations. The noted economist Joseph Stiglitz once said that the challenges faced by globalization sprang from the fact that the rules for globalization were made by rich developed countries mainly for the benefit of the rich developed nations.

JPEPA is worse. It goes beyond WTO because WTO for example prescribed reduced tariffs for nations to follow - but it did not seek total elimination of the same. Under WTO, nations still had a leeway to legislate; under JPEPA we would have no such adjustmemt. WTO did not impose performance requirements for investments. Under JPEPA, we cannot require that the investor hire local labor, promote technology transfer, or use local material for their businesses. WTO did not impose insurance for investments. Under JPEPA we are mandated to guarantee investments against certain risks such as revolution.

When WTO got derailed, some thought that the world would at last listen more closely to the reasons of international protest from developing nations. Now it seems that bilateral agreements embody the new strategies to pursue the advantages of rich developed nations.

The advocates for JPEPA claim that once we approve, trade will increase by 20 % , investments by 350 % . But they do not show a detailed study. They do not explain how or why. On the contrary, a study undertaken by PIDS, Philippine Institute of Development Studies shows that positive growth of the economy arising from JPEPA will be minimal, barely 0.09%. Relatively small. Why? According to an economic analyst because trade is more favorable to Japan and will mainly benefit her, not our farmers and fisherfolks. And Japan’s investments will generally follow the trends of investment -- where transports and infrastructures already exist, not to areas in dire need of investments.

Small benefits – at what price? At the price of the Filipino farmer becoming poorer because he has no real access to the Japanese market, at the price of losing hope for our fishermen, not only because they are being edged out of municipal waters by commercial fishing – but because we open up our exclusive economic zone to Japanese marine enterprises who have the resources to exploit that stretch of sea for themselves.

Above all, the price we must pay if we approve JPEPA is that we relinquish sovereignty to a supposed foreign partner. We cede the right to legislate, we surrender the capacity to protect our own people. We give up the right to govern – and to undertake sustained development. We will be a satellite of Japan.

6. What seems even more abrasive is the proposal in JPEPA, Article 2. It says “With respect to the Philippines, the national territory as defined in Article I of its constitution, the term ‘national terrritory’ also includes the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf to which the Philippines exercises sovereign rights or jurisdiction in accordance with its laws and regulations and international law;”

The second paragraph in the same Article copies the same provision for Japan’s exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, but as in the case of investments – the same one way traffic route prevails - because there hardly exists any Philippine investments in Japan proper, more so in the exclusive economic zone.

The Philippine was granted sovereign rights over Exclusive Economic Zone by the Law of the Sea Conference of the United Nations in the l980s, covering two hundred miles of sea and continental shelf from shoreline to sea. In such areas live fish and aquatic animals, where potential resources like oil and gas and maritime wealth may be found. In the wake of poverties, I have talked to a number of fishermen who live from day to day with their meager catch. They have not even heard of the Exclusive Economic Zone and their potentials, and thought for a while that we were talking of the depletion of municipal waters. But I believe that the nation’s leaders owe it to them to make the areas a living reality for them and their children.

Japan without JPEPA has invested substantially here. Now she wants investments under national treatment, with protection guaranties, plus access to our exclusive economic zone. Will they go fishing there for our benefit? Will they tap the marine resources for our welfare? With due respect I say - Japan has her own exclusive economic zone. Attend to that area. Leave us be.

Section 2 of Article XII of our constitution provides: The State shall protect the nation’s maritime wealth in its archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and EXCLUSIVE ECONOMIC ZONE and RESERVE ITS USE AND ENJOYMENT EXCLUSIVELY TO FILIPINO CITIZENS.” (Capital letters ours) But if we approve JPEPA we accord National Treatment to Japanese Firms to exploit the Two Hundred Mile Area of the exclusive economic zone.

The Petroleum Act, R.A. 387 provides that “all natural deposits or occurrences of petroleum or natural gas ON THE CONTINENTAL SHELF…seaward from the shores of the Philippines…BELONG TO THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES INALIENABLY AND IMPRECRIPTIVELY.” (Capital letters ours)

For all this, it seems only just that we say No to JPEPA. No because we cannot give away what is entrusted. No because the terms embodied therein are basically disadvantageous and unfair to the Philippines and the Filipino. No because we have a mandate to strive for a better legacy to our children. Let us respectfully but firmly say NO to JPEPA!

JULY 4, 2008

VIDEO CLIP- VPTG SPEECH AT CENPEG'S CONFEST

MESSAGE BOARD

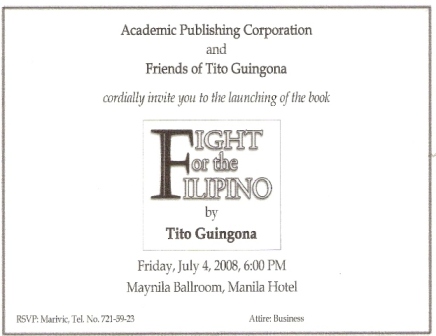

> New Video Presentation. Pictures taken during the launching.

>The "Fight for the Filipino" Book Launching was a huge success. Thanks to all your support!

> The book will be available in National Book Store. you may place your order thru their website. www.nationalbookstore.com

>The Academic Publishing Co. also accepts order and they deliver. Call 9125966. Look for Ms. Lani.

FIGHT FOR THE FILIPINO!

an autobigraphy of Tito Guingona

>The "Fight for the Filipino" Book Launching was a huge success. Thanks to all your support!

> The book will be available in National Book Store. you may place your order thru their website. www.nationalbookstore.com

>The Academic Publishing Co. also accepts order and they deliver. Call 9125966. Look for Ms. Lani.

FIGHT FOR THE FILIPINO!

an autobigraphy of Tito Guingona

VIDEO PRESENTATION

Book Review on "Fight for the Filipino"

Patriot and Activist

By

Carmen Guerrero Nakpil

Only a man “with soul so dead”, wrote the English poet, does not love his native land. All of us claim to love our country. But few love it and its people with the passionate activism and militancy of Teofisto Guingona, Jr. His autobiography, “Fight for the Filipino” is a treatise on patriotism.

In different form and roles, Tito Guingona has been a constant presence in our national life. At different times, he has been a member of the 1971 Constitutional Convention, Chairman of the Commission on Audit, member of the Philippine Senate, Executive Secretary and Secretary of both of Foreign Affairs and of Justice, Vice President of the Republic and Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China. But those are only his formal titles. And, outside of our knowledge of civics and government positions, they tell us very little about Tito Guingona’s total commitment or emotional dynamism. For instance, it is only the last chapter of his 346-page biography that we learn of his latest entitlement to a charge of rebellion earned one afternoon, at the Manila Peninsula Hotel, where he was tear-gassed, arrested, handcuffed and detained.

His saga of fighting for the Filipino begins when he was a 12-year old boy who tagged along on the historic trek taken by President Quezon, his family and some members of his family, including Tito’s father, Commissioner for Mindanao and Sulu, Guingona from Northern Lanao to Bukidnon on the way to Australia in 1942.

It runs through, in vivid detail, through his years as a young student and a neophyte lawyer’s advocacy against the Parity Agreement and the U.S. Military Bases; through his stint in the making of the 1973 Constitution with concomitant arrest and detention during Martial Law; his colorful experiences with Mindanao and Manila partisan politics; his travails and policy differences in the cabinet; his frequent denunciations of anti-Filipino policies and projects; and lastly, his denunciation of a sitting President which caused a regime change.

But I must allow the readers of “Fight for the Filipino”, to discover for themselves the intriguing bits of Philippine history that Tito Guingona describes in the fast-paced, candid, conversational prose of his memoirs. For instance, the incident that happened, only four days after Gloria Arroyo’s take over of Malacañang in 2001, when the new Secretary of Justice, Hernando Perez, whispered in his ear in Tagalog, “She phoned me at midnight to order me to sign the IMPSA contract.” (an anomalous Argentinean contract which President Joseph Estrada had refused to sign because of its sovereign guarantee clause)

There are many other anecdotes and vignettes in this autobiography which makes it, more than intimate personal history, a history of the Philippines and a record of the events and personages of the last 80 years. It is also a manual for the younger generations on how to honor, love and defend this country and its people. There are few better teachers of patriotism than Teofisto (Tito) Guingona, Jr.

Story-telling – the Guingona Way

by

Eggie Apostol

Teofisto Guingona, Jr., one-time Vice-President of the Philippines has many stories to tell. And he tells them in great detail in his book “Fight for the Filipinos”

The stories are so highly detailed that one suspects Tito Guingona keeps a diary. Does he? I have not been able to ask him.

If he doesn’t, then we can only say he has a fantastic memory. And it is just as well for the telling of his life is like a recollection of our nation’s history.

Focus is, of course, on Mindanao – where his own father like him served as senator and later Commissioner for Mindanao and Sulu.

For those who lived all their lives in Luzon (or in the Visayas for that matter) the goings-on in Mindanao are like happenings in a foreign country. Because the country is mostly Christian but Mindanao has a sizeable number of Muslims (nine thousand about 50 years ago) mostly due to its proximity to Borneo and Indonesia.

One cannot help but envy the Guingona family for growing-up in the most beautiful part of the country – the Lake Lanao area.

This was so beautiful that when President Quezon saw it he asked that a branch of the Manila Hotel be built there. Which was done.

Although his family was anchored in Mindanao, Guingona studied in the Ateneo de Manila so that later in life he hobnobbed with Raul Manglapus, Diosdado Macapagal, Joe Calderon and Caesar Espiritu, Carlos Garcia and Jun Puyat. When problems came up about the Mindanao area he was always the Mindanao expert for solutions.

Guingona relates during Marcos’ martial rule:”one evening over a secretive dinner, where Fathers Horacio de la Costa and Jaime Bulatao were present, one of our conservative members of the group said: “The real response to martial rule is rebellion, but I’d like to know from our religious Fathers here – whether rebellion is morally justified?” The question was a riser; it was not said in a jest, and one of the priests curtly replied “Don’t worry, we’ll find a way to justify it.” That broke the ice and resulted in laughter.

Guingona’s life had its share of ironies. Before EDSA I he joined Cory in boycotting products linked to Malacañan, “I challenge the crowd not to pay their Meralco bill. Seven days later after our victory with Cory she appointed me president of Meralco. So I called for another big meeting and told the people ”Times have changed – pay your Meralco bills!”

Guingona liked to encourage better relations with Chinese in the Philippines. He submitted some suggestions: 1) Enhance herbal medicine in the Philippines, with Chinese help 2) Plant cassava or cash crops between spaces of coconut trees. 3) generates jobs by adopting the policy of giving value added to native products 4) Encourage technology connected to giving added value to coconut, fruits and fish; 5) encourage tourism by building necessary infrastructures 6) implement joint economic ventures.

Readers will be reminded that Guingona was a political activist from the start. When he was made Chairman of the Commission on Audit he was also a peace negotiator. When President Ramos made him executive secretary he grappled with the ADC and Jai Alai and the Flor Contemplacion case. He actively joined the fight for justice in the Vizconde massacre, the Jalosjos case, the Fr. Shay Cullen problem, the Maysilo Estate case, the Alfredo Tiongco case, U.S. property claim in Fort Bonifacio, the Textbook scam, the Visiting Forces Agreement, the WTO and GATT.

As Vice-President and Secretary of Foreign Affairs he was involved in 9/11 and the VFA, the IMPSA controversy, concern for the OFW’s and attending to foreign travel commitments. He differed with Malacañang in in pursuing OFW and Steel mill programs. He said No to Bush’s war in Iraq.

At book’s end, Guingona is very much in a negative mode: He sees in the Gloria Arroyo regime much that he finds dishonest. He had been asked by President Arroyo to become the new Ambassador to China which he accepted.

But the “Hello Garci” tapes was unraveled and proved that President Arroyo had tampered with the elections. Guingona did not want to continue with his new assignment and resigned.

“We must reform” is his current and latest plan.

INVITATION

BOOK

Pls. call us for resevation.

BOOKS

THE GALLANT FILIPINO

A nation is poorer by so much everytime one of its heroes passes into oblivion. For as Tito Guingona, Jr. writes "the true treasures of the Filipino are not gold or silver" They are the men and women whose heroic lives would bring back to us in a book. And so Tito Guingona has written The Gallant Filipino...

LABAN - VOICE OF RESISTANCE

On Sept. 21, 1972 Ferdinand E. Marcos imposed martial rule in the Philippines. It marked the beginning of a black chapter in the nation's story. On Aug. 21, 1983 they killed Benigno S. Aquino. His death inflamed the nation, and it marked the beginning of the end for Mr. Marcos. From then on the people demanded back their rights. they rallied. they marched. They defied the guns and tanks and bullets of the dictator - in the end, they defended the soldiers who rose in revolution. In that crucial hour, the nation triumphed...

FACE THE CHALLENGE

To the small Filipino businessman - whose continuing strife to survive deserves sustained support. May he eventually succeed - if not under the present economic system - then in another more responsive to the nation's needs!

A nation is poorer by so much everytime one of its heroes passes into oblivion. For as Tito Guingona, Jr. writes "the true treasures of the Filipino are not gold or silver" They are the men and women whose heroic lives would bring back to us in a book. And so Tito Guingona has written The Gallant Filipino...

LABAN - VOICE OF RESISTANCE

On Sept. 21, 1972 Ferdinand E. Marcos imposed martial rule in the Philippines. It marked the beginning of a black chapter in the nation's story. On Aug. 21, 1983 they killed Benigno S. Aquino. His death inflamed the nation, and it marked the beginning of the end for Mr. Marcos. From then on the people demanded back their rights. they rallied. they marched. They defied the guns and tanks and bullets of the dictator - in the end, they defended the soldiers who rose in revolution. In that crucial hour, the nation triumphed...

FACE THE CHALLENGE

To the small Filipino businessman - whose continuing strife to survive deserves sustained support. May he eventually succeed - if not under the present economic system - then in another more responsive to the nation's needs!

Vice President

Tito Profile

Teofisto T. Guingona, Jr. reached a new high in his stellar career when both Houses of Congress confirmed his nomination as Vice President of the Philippines by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

Born in San Juan, Rizal on July 4, 1928 to Teofisto Guingona, Sr., a former assemblyman, senator, judge and commissioner from Guimaras, Iloilo and Josefa Tayko of Siaton, Negros Oriental, he grew up in Mindanao where he completed his elementary schooling with honors in Ateneo de Cagayan.

He pursued his studies at the Ateneo de Manila University as a working student, teaching history and political science while taking up courses in law and economics. He took up special studies in Public Administration, Economics, Sociology and Audit. After graduation, Tito went into business and became a Governor of the Development Bank of the Philippines and President of the Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines.

Tito was a delegate to the 1971 Constitutional Convention and when Martial Law was declared in 1972, he staunchly resisted the abuses of the regime, serving as a human rights lawyer and defender of the oppressed. He founded SANDATA and became the honorary chairman of BANDILA, two mass-based organizations dedicated to social and economic reforms. Because of his opposition to martial rule he was jailed twice, first in 1972 and then in 1978.

When the dictator was ousted, the new President appointed Tito as Chairman of the Commission on Audit where he gained renown as a no-nonsense graft buster. He did not stay long in the Commission on Audit, however, for he was drafted to run for a Senate seat. In the Senate, Tito was Senate President Pro-tempore and Majority Leader. He also chaired the Blue Ribbon Committee.

Tito’s concern for the welfare of his kababayans in Mindanao is apparent when he served as director and chairman of the Mindanao Development Authority and the Mindanao Labor Management Advisory Council respectively.

Born in San Juan, Rizal on July 4, 1928 to Teofisto Guingona, Sr., a former assemblyman, senator, judge and commissioner from Guimaras, Iloilo and Josefa Tayko of Siaton, Negros Oriental, he grew up in Mindanao where he completed his elementary schooling with honors in Ateneo de Cagayan.

He pursued his studies at the Ateneo de Manila University as a working student, teaching history and political science while taking up courses in law and economics. He took up special studies in Public Administration, Economics, Sociology and Audit. After graduation, Tito went into business and became a Governor of the Development Bank of the Philippines and President of the Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines.

Tito was a delegate to the 1971 Constitutional Convention and when Martial Law was declared in 1972, he staunchly resisted the abuses of the regime, serving as a human rights lawyer and defender of the oppressed. He founded SANDATA and became the honorary chairman of BANDILA, two mass-based organizations dedicated to social and economic reforms. Because of his opposition to martial rule he was jailed twice, first in 1972 and then in 1978.

When the dictator was ousted, the new President appointed Tito as Chairman of the Commission on Audit where he gained renown as a no-nonsense graft buster. He did not stay long in the Commission on Audit, however, for he was drafted to run for a Senate seat. In the Senate, Tito was Senate President Pro-tempore and Majority Leader. He also chaired the Blue Ribbon Committee.

Tito’s concern for the welfare of his kababayans in Mindanao is apparent when he served as director and chairman of the Mindanao Development Authority and the Mindanao Labor Management Advisory Council respectively.

the senator at work

i survived martial law

Anti GMA Rally

Water Canonized by the Police

About the Peninsula Seige/ An Interview with Karen Davila

Friday, April 18, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment